Books on Writing 101: Jeff VanderMeer's "Wonderbook" (Non-fiction, Writing craft)

Books on writing 101 is a collection of book recommendations to get you started on writing. Inspirational, insightful, and entertaining books I’ve enjoyed that will help you find your own way. Everyone learns differently, but this is how I started:

Jeff VanderMeer’s “Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction”

If I had to recommend one book to a new writer, especially one who wants to work in the world of science fiction, fantasy, or weird fiction, it would be Wonderbook. Jeff VanderMeer is the author of fantastic works of poetic and devastating genre books like Annihilation (and the entire Southern Reach Trilogy), Borne, and Dead Astronauts - all of which are filled to the brim with not only vivid and horrifying imagery, but huge amounts of depth and message. Wonderbook dives deep into craft, life, and the writer’s imagination. From guest essays by Neil Gaiman, George R.R. Martin, and Ursula le Guin, to centerfold illustrations on the depths of story structure, the book provides many avenues to create real and imaginative fiction. What I like most about the book is that it has many perspectives. There isn’t one way to do something when you write - often, there isn’t one way to do something from book to book even - so to provide a framework of encouragement, craft knowledge, and opportunity is a gift to a new writer.

“You can’t be inspired every day, just like you can’t be madly, deeply, insanely in love every day. But how such moments manifest as you move through the world and the world moves through you defines the core of your creativity.” (pg. 2)

The opening chapter is “Inspiration and the Creative Life.” At the heart of any practice, there has to be inspiration. This can come in short bursts, or lifelong avenues of wildly vivid thought. But no matter the inspiration you currently have, you must work to maintain it for very long periods, especially as you begin to write seriously. Most people don’t have the luxury of time when they start - even students have to contend with other classes, a social life, and their impending life as a working person - so you have to make the space for inspiration to last and dwell within.

I often write in the evening after work. During COVID-19, this has been a lot harder. Work is longer and more stressful than before, so when I come home I need to escape. To be outside of my mind, I often resort to endless hours of television. Not writing. But when I sit down to write, I need that inspiration to be there too. When you work this way, there isn’t a lot of space to wait for that creativity and inspiration to come. So you work on it all the time. I keep a notebook on me, always, and I think about my stories in idle moments. I develop them in my mind, and then on scraps of paper throughout the day. So when the time comes, there is something to work with.

“The most important thing is allowing the subconscious mind to engage in a kind of play that leads to making the connections necessary to create narrative.” (pg. 8)

There is the infamous shower moment. You’re working on something, you’re stuck, you can’t move forward. You sleep on it, you do something else. Then, in the shower, BAM! You’ve found the solution, and inspiration is back. The wheels are back on the bus. This happens to me a lot. I often write in the evening, some time between post-dinner and pre-sleep. I also shower in the evening, often last minute when I remember how gross of a person I am. So I give up writing for the evening, with the plan to shower and then watch some TV and go to bed. But then! Of course. Out of nowhere, my resting mind says: “Buddy, I’ve figured it out. The answer was simple all along,” and I have to go back to writing. Sometimes this answer is easy. Sometimes it would take many hours of retreading and revision to make a reality. In the latter case, I often take out a Foolscap page and jot down whatever comes to mind in a kind of crazed mind-dump prose. This way I not only remember the revelation, but also the situation it came to life in. I don’t always re-read these notes, but the simple act of giving them space helps me to remember (and sleep easy knowing I at least wrote them somewhere). [As an aside: please write down everything. Carry a notebook. Keep one by the bed. In your bag. In the bathroom. Ideas evaporate quickly.]

“The reader only cares about what he or she experiences on the page. That’s why you must not mistake the progress of your inspiration for the actual progress of the story. The scene that sparked your desire to create fiction may not be the starting point of the story, and the story itself may not even be about what you thought it was about when you wrote the opening.” (p 75)

Those ideas from the night before are not the story. Or even the start of the story. Or even exact moments in the story. I jot them down manically so I can remember the tone and the context and the madness that will build the future story. This, for me, is a new practice. As someone who is a recovering Discovery Writer (someone who does not outline, instead choosing to let inspiration and character lead them into a blank future), I often found that, even in reverse outlining, I was missing the kind of depth and plot needed to make a longer story work. In short fiction, discovery writing worked very well for me. It allowed a strange and mysterious world to emerge (partly because it was strange and mysterious to me too!), but when you start to expand into longer stories - the story elements become more challenging. Things need to be internally consistent. In order to satisfy this discovery practice in my longer work, I’ve been free writing tons of character and scene moments that are pure inspiration. No worry for structure, or consistency, or even character names - just whatever comes out. I dump onto physical paper. This helps me to develop a world, and a handful of people in that world, to then build a properly structured story around and, like the shower moment, this provides a space for inspiration to come through. It’s a meditation.

“You should approach an understanding of story elements not as if you were approaching a puzzle that, once solved, will never need to be solved again, but so you can create something wonderful or deadly or harrowing or tragic or melancholy.” (p. 72)

No matter which genre you are writing in, I highly recommend Jeff VanderMeer’s Wonderbook. It is great for a new or experienced writer. The revised & expanded edition is out now from Abrams Image.

Keep your eyes out for more Books on Writing 101! The 101 series are books that I think are a great place to start if you know nothing about writing and want to get started. Nothing too wild, but still packed with wonderful tips and insight.

Previous post in this series:

Haruki Murakami’s “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running”

Books on Writing 101: Derrick Jensen's "Walking on Water" (Non-fiction, Writing craft)

Books on writing 101 is a collection of book recommendations to get you started on writing. Inspirational, insightful, and entertaining books I’ve enjoyed that will help you find your own way. Everyone learns differently, but this is how I started:

Derrick Jensen’s Walking on Water

If Steering the Craft is a workshop in a book, Walking on Water is a reflection on having taught. Derrick Jensen is a rather radical (and sometimes brash) person/teacher/writer, so to say take this book with a grain of salt will be, for some, an understatement. It will not be for everyone. But sometimes these are the kinds of books you learn from the most.

I read Derrick Jensen’s The Culture of Make Believe, and then Walking on Water, at a time in my life when I desperately needed something to change. I was looking for activism, I was looking to have my mind blown, and above all I was looking for some goddamn answers. There are a lot of areas in life that seem like endless voids of that’s just the way it is. School, for a long time, felt this way. In Hawaii, where I finished middle school and about half of high school, education felt needlessly stale (hopeless, to put it nicely). Due to generations of defunding and devaluing education, not to mention extremely fresh colonialism, the schools fell into a pattern of group learning and the very basics of education. There wasn’t time to individualize. There wasn’t space to ensure that every child got at least the minimum of what they needed to believe there was a purpose to education. A lot of my friends left school before their junior year, to get a GED, to attend “online school,” to start working, which is no surprise when I think back to the many hours spent in special school counseling sessions, art classes rooms, and hiding behind the tennis court to smoke cigarettes. Maybe this isn’t unique, but it was certainly very discouraging.

“We hear, more or less constantly, that schools are failing in their mandate. Nothing could be more wrong. Schools are succeeding all too well, accomplishing precisely their purpose… the truth is that our society values money above all else, in part because it represents power, and in part because, as is also true of power, it gives the illusion that we can get what we want. But one of the costs of following money is that in order to acquire it, we so often have to give ourselves away to whomever has money to give in return. Bosses, corporations, men with nice cars, women in power suits. Teachers. Not that teachers have money, but in the classroom they have what money elsewhere represents: power.” (p. 5-6)

I see you rolling your eyes, Yes, it is that kind of book. And if you’re 30-something, hopefully you’ve come to this conclusion already. But I first read this when I was 22 years old and on the cusp of losing my mind with work and life. Community College was an extension of high school and money came from working longer hours more often. Quitting college to become an assistant manager at Hot Topic at the mall, to get my own place, to live away from school and parents and start “life.” These are the kinds of books that can take you in one of two paths: radicalized, learned, curious or nihilistic and helpless. In a way I hope you’ve experienced both. I am a deeply cynical person. In my mind, before anything else, there is the negative and a book like this encourages that sometimes. But it also is enlightening and provides the framework for answering things about yourself. What happened to you. These lessons come much later, of course, if at all.

I think writing is about exploring that even deeper. In Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird, she says to start with the earliest memory you have and try to write from there - to explore your early life, to explore yourself. It forces you to think deeply about painful things, and happy things, and weird things that happened to you, so you can use those experiences to develop a character. A living thing outside of yourself to which other people can relate.

“My main problem was that my storytelling was false. I didn’t yet understand that in order to write something good, or to tell a good story, I didn’t have to invent something fantastic. I simply had to be as much of myself as possible.” (p. 27)

Whether you are a writer, a teacher, or someone just starting to think about being creative. I recommend reading Walking on Water, if only to start to understand how to see teaching and learning differently. You may know all this already, it might be late enough in your life and learning that this is all galaxy-brain-meme-worthy text. But just in case it isn’t, check this book out from your library. Read it with some awareness of the author, but read it nonetheless.

Keep your eyes out for more Books on Writing 101 next week! The 101 series are books that I think are a great place to start if you know nothing about writing and want to get started. Nothing too wild, but still packed with wonderful tips and insight.

Previous post in this series:

Haruki Murakami’s “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running”

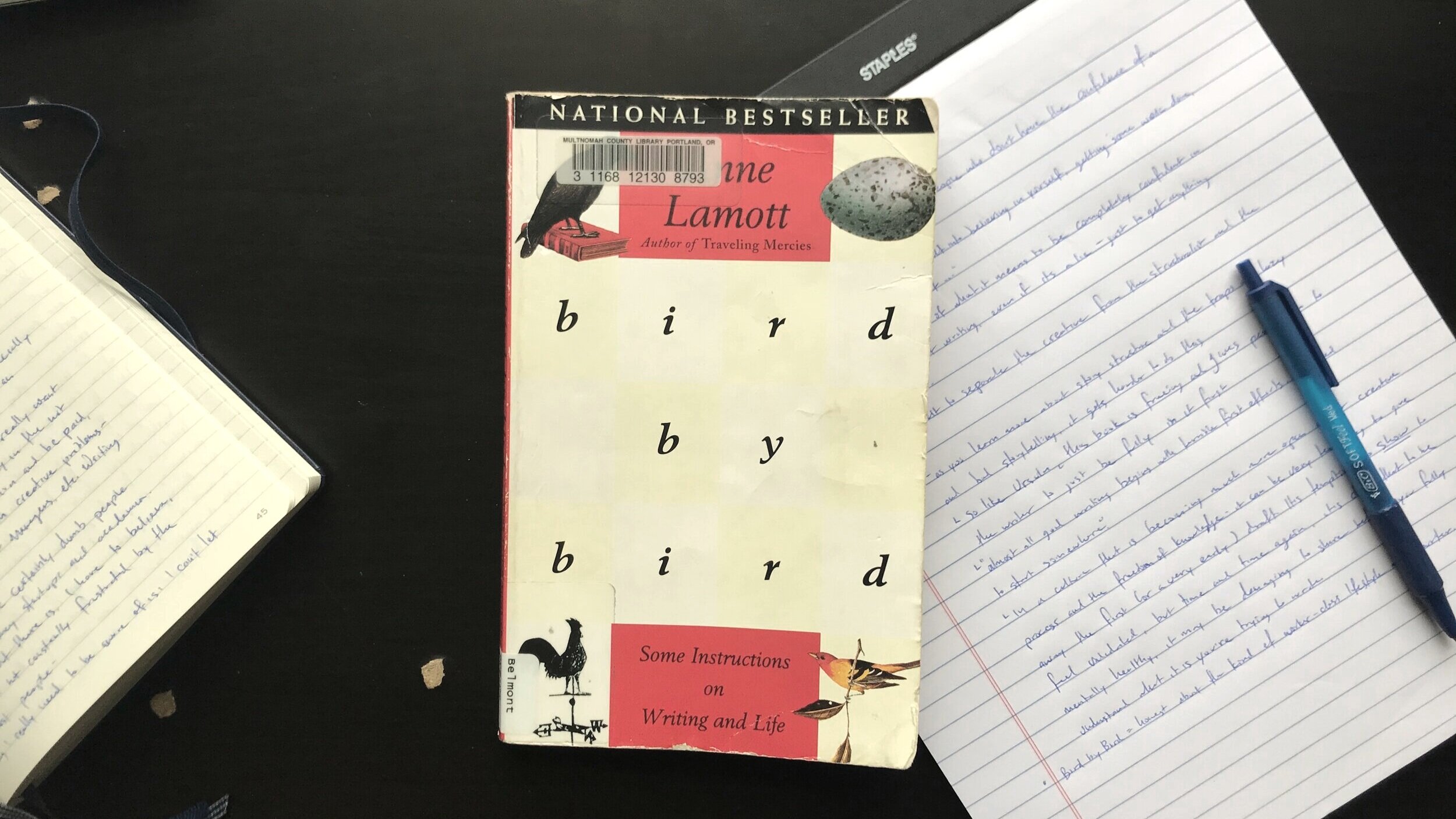

Books on Writing 101: Anne Lamott's "Bird by Bird" (Non-fiction, Writing Craft)

As in Ursula K. Le Guin's *Steering the Craft*, the idea of hypnotizing yourself into creating with confidence is something you don't hear often in writing lessons - or at least, you don't hear said quite this way. It gives a sense of play and freedom. Just trick yourself for a while into doing this thing, then, when you're ready, put on a different hat.

Books on writing 101 is a collection of book recommendations to get you started on writing. Inspirational, insightful, and entertaining books I’ve enjoyed that will help you find your own way. Everyone learns differently, but this is how I started:

Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird

“Writing is about hypnotizing yourself into believing in yourself, getting some work done, then unhypnotizing yourself and going over the material coldly.” (p.26) From a chapter called: Broccoli

As you learn more about story structure, and the traps of lazy or bad writing, it becomes increasingly hard to hypnotize yourself into just creating something. Bird by Bird is a book that sets out to emphasize: you will be bad, probably forever. Even if you get good, you will think you're still bad. I find this sentiment comforting because for a long time it feels like a skill you get good at and then... professionalism happens. You get published, you get work, it become effortless and nice and even joyful to write. But Anne goes back to this thought in many chapters to give you a dose of reality (along with, thankfully, a cure).

"Almost all good writing begins with terrible first drafts. You need to start somewhere... A friend of mine says that the first draft is the down draft - you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft - you fix it up [...] And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it's loose or cramped or decayed, or even, God help us, healthy." (p.26) Shitty First Drafts

In a culture that has becoming increasingly open about creative process and the freedom of knowledge, it can be tempting to give away the first draft (or the second or third draft, for that matter) before it's time. I've been thinking a lot about open culture and how much better creating is now than it might have been 30 years ago. YouTube and Blog Culture have opened up the creative process to ensure that people who want to create, can create - they have the resources to at least see how someone else does it. I really like that. But it can definitely be tempting to document all of the gross first-thought kind of work that goes into something like writing, or music, or illustration. I feel like with illustration, or other visual art crafts, it's much easier to explain: "I'm working on faces this year, I feel really bad about these, but look... there's improvement here. Here's what I learned." But with writing I find it much harder to feel open enough to say: "I'm working on dialogue right now. Please watch me skim through a library of books to see how the masters do it. Fail to do it myself. Watch Netflix like a psychopath - stopping, writing down character interactions, backing up again, starting again, writing more things down... and hope I get better.”

Along with this, it is very tempting to show people your early work for the sense of validation it brings. "Look, I know this is an early draft, but I wanted to share something." The real trap here is that *it's too early* to get feedback. You know the story doesn't work yet. You know you're still hypnotized into feeling like you did a fantastic job and that you are a fucking genius. But if you wait a week, and read it again like you're supposed to, (to unhypnotize yourself), you'll see it isn't ready. The kind of feedback you may get at this point could be devastating to the process. It often sends me down a rabbit hole of self-doubt or, worse, egoistic betrayal. "They just don't get it, those fools! What do they know about story!?"

As in Ursula K. Le Guin's *Steering the Craft*, the idea of hypnotizing yourself into creating with confidence is something you don't hear often in writing lessons - or at least, you don't hear it said quite this way. It gives a sense of play and freedom. Just trick yourself for a while into doing this thing, then, when you're ready, put on a different hat.

This is still difficult for me. Putting on the metaphorical Creator Hat, which ignores all spelling errors, and story structure mistakes, and character voice, and how a brother in one scene became a sister later in the piece... It's hard to just plow forward, knowing later that you'll come back with the Editor Hat and fix it.

When we interviewed Cory Doctorow for the Talking to Ghosts podcast, he told us about "TK"-ing a detail and then moving on to whatever you were writing. I think this is pretty common knowledge among folks who write regularly, but I didn't know about it at the time. The idea of "TK"-ing something is this: You are writing, you're speeding through, you're in the moment, but you can't remember the eye color of your main love interest, which was set 20 pages ago... Instead of stopping and going back through all the files to find that note, or that eye color, or whatever, you just put "[tk: eye color]" and keep on writing. When the draft is done, during editing, you can search "tk" and get all of the things you need to add back in. "Tk" stands for To Come, but they use "t" and "k" because "tk" doesn't appear in other words, so it's easier to find. If you were to use "tc" you'd get search results for words like "ouTCome" as well. It saves time.

I don't do this enough. I should, but I don't. Because my writing times are so sporadic, I don't really have the time to go back through all the documents anyway. But if you're a good writing student, who actually sets time aside to write in a nice, quiet environment, I definitely recommend getting in the habit. Do whatever you can to not break focus and flow.

Parting words from Anne:

"Publication is not going to change your life or solve your problems. Publication will not make you more confident or more beautiful, and it will probably not make you any richer... Let's discuss some other reasons to write that may surprise a writer, even a writer who hasn't given up on getting published." (p.185)

What follows is a motivational chapter on why you should write for yourself and, if you write for others, why it should be special. Definitely check out this book. If you are in Multnomah County, check it out from the library!

Keep your eyes out for more Books on Writing 101 next week! The 101 series are books that I think are a great place to start if you know nothing about writing and want to get started. Nothing too wild, but still packed with wonderful tips and insight.

Previous post in this series:

Haruki Murakami’s “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running”

Books on Writing 101: Ursula K. Le Guin’s "Steering the Craft" (Non-Fiction, Writing Craft)

Originally released in 1998, Steering the Craft is a workshop in book form. Filled to the brim with amazing exploratory writing exercises, examples, and tips, this book will get you unstuck from almost any problem you’ll have when starting to write narrative for the first time.

Books on writing 101 is a collection of book recommendations to get you started on writing. Inspirational, insightful, and entertaining books I’ve enjoyed that will help you find your own way. Everyone learns differently, but this is how I started:

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Steering the Craft: A 21st-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story

Originally released in 1998, Steering the Craft is a workshop in book form. Filled to the brim with amazing exploratory writing exercises, examples, and tips, this book will get you unstuck from almost any problem you’ll have when starting to write narrative for the first time.

“The exercises are consciousness-raisers: their aim is to clarify and intensify your awareness of certain elements of prose writing.” (p. xii)

In the first chapter, The Sound of Your Writing, Le Guin compels her audience to be gorgeous, just for the pleasure of it. She says:

“Being Gorgeous is a highly repeatable exercise… and can serve as a warm-up to writing. Try to set a mood by using verbal sound effects. Look at the view out the window or the mess on the desk, or remember something that happened yesterday or something weird that somebody said, and make a gorgeous sentence or two or three out of it. It might get you into the swing.” (p. 10)

While this advice might seem simple for some writers, it sets the book outside of most writing craft books pretty early. Ask any author when they were last given permission to just be playful with their writing in school, or at a workshop, and I would be willing to bet you’ll get a series of blank looks. So much of learning the craft of writing is intense focus and technical structure - over and over again it amounts to the feeling of never having read, or tried hard, enough. So to be given permission to just play and be gorgeous is something special.

To give a related example: Chapter 4 is on repetition:

“…to make a rule never to use the same word twice in one paragraph, or to state flatly that repetition is to be avoided, is to go against the nature of narrative prose.” (p. 37)

Le Guin speaks plainly about the flaws in a piece of writing that uses repetition in a way that makes the text distracting, but is careful to say it is also a way to develop voice and wonderful prose. In the end, like all things, it comes down to practice and learning from examples (of which she gives: “The Thunder Badger” from W. L. Marsden’s Northern Paiute Language of Oregon, and “Little Dorrit” by Charles Dickens).

The exercise for this chapter, to give you an example, is:

“Write a paragraph of narrative (150 words) that includes at least 3 repetitions of a noun, verb, or adjective (a noticeable word, not an invisible one like was, said, did.)” (p. 41)

“…In critiquing, you might concentrate on the effectiveness of the repetitions and their obviousness or subtlety.” (p.42)

When I purchased this book, I have to admit, I was not ready for it. It took me a few years to truly understand the pleasure of these exercises and examples. At the time, I was full of ego and drive, but not ready to learn the things I wasn’t immediately interested in (like how to use POV, or what she calls “crowding and leaping,” which is a way to edit and compress structure during revisions). It wasn’t until I decided to re-read it for this series that I was truly open to what Ursula, wisely, was trying to say.

So if you are leading a workshop, or stuck in a spiral of blocked writing (hoping to get out), I would definitely encourage you to pick up Steering the Craft.

Keep your eyes out for more Books on Writing 101 next week! The 101 series are books that I think are a great place to start if you know nothing about writing and want to get started. Nothing too wild, but still packed with wonderful tips and insight.

Previous post in this series:

Haruki Murakami’s “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running”

Books on Writing 101: Haruki Murakami's "What I Talk About When I Talk About Running" (Non-fiction, Writing Craft)

If On Writing was a collection of anecdotes centered around a writer’s life and craft, Haruki Murakami’s What I Talk About When I Talk About Running is a travel journal told in the structure of The Hero’s Journey. It would be almost impossible, I believe, for a novelist to write a memoir - even one centered around the need to complete triathlons and ultra-marathons - and not talk about their writing life.

Books on writing 101 is a collection of book recommendations to get you started on writing. Inspirational, insightful, and entertaining books I’ve enjoyed that will help you find your own way. Everyone learns differently, but this is how I started:

Haruki Murakami’s What I Talk About When I Talk About Running

Hardcover edition of “What I Talk About…”

If On Writing was a collection of anecdotes centered around a writer’s life and craft, Haruki Murakami’s What I Talk About When I Talk About Running is a travel journal told in the structure of The Hero’s Journey. It would be almost impossible, I believe, for a novelist to write a memoir - even one centered around the need to complete triathlons and ultra-marathons - and not talk about their writing life.

Perhaps best known for his magical realist fiction, Murakami dives deep into why he runs - at one point saying “I run in order to acquire a void” (p. 17) - and how it has helped him write novels. He believes great stamina and endurance is needed to complete a good novel, then start again with another. It’s hard work. He says:

“I have to pound the rock with a chisel and dig out a deep hole before I can locate the source of creativity. To write a novel I have to drive myself hard physically and use a lot of time and effort.” (p. 43)

While he had pretty immediate success with his first novel, which was hand written and sent into a contest (which he won), Murakami is clear that some people have a natural wellspring of talent, and others have to work hard to get there. One thing that stood out to me about his early career, hidden behind some ridiculous luck and missing information, is that he started to translate things like Raymond Carver into Japanese. This kind of deep focus on a masterwork builds skill and awareness, especially when you are having to think creatively about how to make the meaning work in a different language and culture. Often I hear advice, which basically amounts to: retype your favorite book, just to get the physical feeling of making the words appear. I haven’t tried this myself (mostly because it seems like a lot of time spent not creating new work), but if you’re struggling with structure or sentence construction, I hear it helps!

“I only began to enjoy studying after I got through the educational system and became a so-called member of society. If something interested me, and I could study it at my own pace and approach it the way I liked, I was pretty efficient at acquiring knowledge and skills.” (p. 35)

I never finished college. There are some credits, somewhere, aging on a community college registry. I liked a lot of classes, especially after I stopped following the general degree path and dove into philosophy and sociology classes. But through staying curious and reading, I learn a lot. I try to let myself be interested in many different subjects, mostly creative and writing subjects these days, but I also try to listen. Writing is about following ideas into dark places, learning about things (whether they are emotional things or physical things) you might never have thought about. This is a new realization for me. I’m sure you came to it much sooner than I did, but I never understood the amount of deep thought work that went into writing. Not only is there intentionality in creating fiction, but there’s also a need to get deeply into the whys of the world.

“…the next most important quality [after talent] is for a novelist [to have] focus - the ability to concentrate all your limited talents on whatever’s critical at the moment. Without that you can’t accomplish anything of value… Even a novelist who has a lot of talent and a mind full of great ideas probably can’t write a thing if, for instance, he’s suffering a lot of pain from a cavity.” (p. 77)

Open Book with flagged pages

The Hero’s Journey of What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, surrounds Murakami’s failure to complete a triathlon he’d been training for for a long time. He’s completed marathons and ultra-marathons and even some triathlons, but at some point everyone fails. His road of trials begins when he has to re-learn how to swim (having been self-taught originally) and wait for the next triathlon season to come around. In the end, of course, he finishes the race and is happy with his time - then he competes again, how could he resist? And while this may seem like the kind of memoir you wouldn’t be too interested in if you weren’t a runner, you’d be wrong. It’s interesting and personal, it’s compelling in the same ways his novels are compelling. It’s good writing that no one was really asking for (he says), but that was personal to his experience. In the end, upon re-reading What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, I came away with a lot of writing advice, but also the idea that even personal travel journals can have good structure.

“…I didn’t start running because somebody asked me to become a runner. Just like I didn’t become a novelist because someone asked me to. One day, out of the blue, I wanted to write a novel. And one day, out of the blue, I started to run - simply because I wanted to. I’ve always done whatever I felt like doing in life. People may try to stop me, and convince me I’m wrong, but I won’t change.” (p. 150)

Keep your eyes out for more Books on Writing 101 next week! The 101 series are books that I think are a great place to start if you know nothing about writing and want to get started. Nothing too wild, but still packed with wonderful tips and insight.

Previous post in this series:

Books on Writing 101: Stephen King's "On Writing" (Non-Fiction, Writing Craft)

On Writing is, like many great writing craft books, mostly memoir. King is the master of funny and strange stories, and this book is filled with all kinds of anecdotes about a writer’s life, rejection, and what it’s like, on a day-to-day level, to have a job, and a family, while trying to learn how to write.

Books on writing 101 is a collection of recommendations to get you started on writing. Inspirational, insightful, and entertaining books I’ve enjoyed that will help you find your own way. Everyone learns differently, but this is how I started:

Stephen King’s On Writing

On Writing, like many great writing craft books, is mostly memoir. King is the master of funny and strange stories, and this book is filled with all kinds of anecdotes about a writer’s life, rejection, and what it’s like, on a day-to-day level, to have a job, and a family, while trying to learn how to write.

While discussing how much he writes, King gives the writing habits of the English author Anthony Trollope as an example:

“His day job was as a clerk in the British Postal Department; he wrote for two and a half hours each morning before leaving for work. This schedule was ironclad. If he was in mid-sentence when the two and a half hours expired, he left that sentence unfinished until the next morning. And if he happened to finish one of his six-hundred-page heavyweights with fifteen minutes remaining, he wrote “the end,” set the manuscript aside, and began work on the next book.” (p.147)

Like most beginning writers in their thirties, I have a day job and I work a lot. There isn’t always time for writing (or, more honestly, there isn’t always the mental space that writing needs). I get up at five-thirty and get home around six in the evening. On weekends, I try to fit writing in where I can – mostly in the morning or afternoon, when the ideas are fresh, and the coffee is still working. But since the pandemic hit, I’ve been trying to make time in the evenings. At a particularly busy and stressful period of work, I realized the few hours I was able to get writing done on the weekends weren’t enough. So, I made a plan: most weeknights, after dinner and a little TV, I’d sit down at the kitchen table for at least an hour and try to work on something. It wasn’t always writing, but it was something. When I didn’t feel like I could write, I tried to read or study different craft books.

On reading, King says:

“If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write – simple as that.” (p. 142)

On Writing is an inspirational and hugely entertaining book, even if you aren’t looking to learn how to become a better writer, which is something I think is very important. So many people have picked this book up and thought, Wow, I think I want to try that, which is the success of any good writing book.

There’s an aside I hear repeated a lot in writing conversations, which comes from a part of On Writing about ideas and subjects – basically: if you’re a plumber who enjoys science fiction, writing about a plumber on a spaceship… etc. But I find what comes right before this quote more enlightening:

“Write what you like, then imbue it with life and make it unique by blending in your own personal knowledge of life, friendship, relationships, sex, and work. Especially work. People love to read about work.” (p. 157)

It isn’t always easy to sit down and write about what you know - or come up with new ideas - especially when you’ve spent all day building spreadsheets. Mindless, endless, spreadsheets. But this advice still holds. Instead of work, you could write a cautionary tale about mindlessness or perhaps about an action scene that takes place in the tight cubicle corridor you know so well. (“How would I get off the roof?” you have to ask yourself.) Even in those experimental moments, when you don’t know what to write - keep writing, see if you can make it into something.

“When I’m writing,” King says, “it’s all the playground, and the worst three hours I ever spent there were still pretty damned good.” (p. 149)

Keep your eyes out for more Books on Writing 101 next week! The 101 series are books that I think are a great place to start if you know nothing about writing and want to get started. Nothing too wild, but still packed with wonderful tips and insight.

Also, please let me in the comments what your favorite books on writing are!