Story: Small Towns, Modern Loneliness

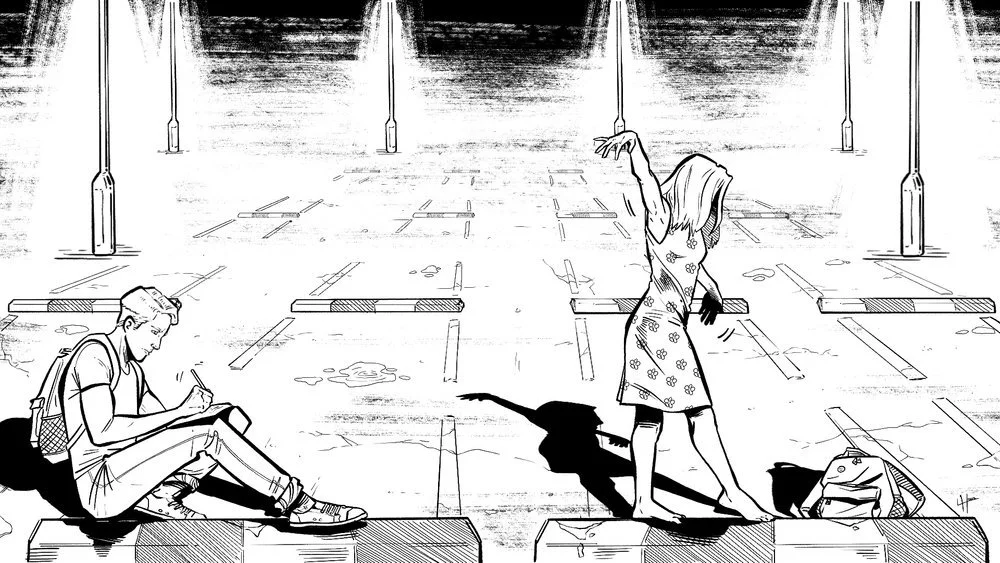

A new short story, written by Michael Kurt with an illustration by Laura Helsby! As summer starts, Hailey Serton reflects on the end of high school and who she’ll be in college.

Written by Michael Kurt | Cover Illustration: Laura Helsby

Description: As summer starts, Hailey Serton reflects on the end of high school and who she’ll be in college.

An Excerpt

Hailey Serton’s mother annoyed the shit out of her. Despite the many years they’d spent living in a small apartment, they had not become bonded by their shared experience of her teenage life. So when she got home late from the Melville Shakespeare Festival, Hailey gave the living room a wide berth in hopes that the undoubtedly strong smell of cigarettes could not be detected on her summer dress.

“Did you have a good time?” her mother called, turning away from what she was watching on the living room TV.

She had not had a good time, actually, but was too tired and too dirty to be trapped in a conversation about it. “Sure,” she called back.

There was a pretentiousness to anything Shakespearean around which Hailey could never fully relax, despite many years of community and high school theater. Fern Michaels, who had asked her to take the bus with him to Melville, thought she might like it, which, given the kind of person she was, was not entirely surprising, but deeply disheartening.

Hailey’s mother followed her almost all the way into the bathroom. “How was the bus?”

“It was a long trip. Especially back,” she replied, closing the door.

When Hailey met Fern last year, she was quickly able to convince him to wait with her in the parking lot after rehearsals. Her mother was chronically late and Fern was chronically lonely, so she was doing him a favor. What she did not expect, however, was that Fern’s mother would circle the school for a half hour before finally offering to drive her home. So, by the time Fern asked her to go to the festival with him, she felt that she’d owed him many times over.

Through the bathroom door, Hailey’s mother asked: “Did he try anything?”

“Who?”

“That boy.” Her mother didn’t like his name, and avoided saying it. “Fern, or whatever.”

“Did Fern try anything at the Shakespeare Festival in the middle of a crowd of theater dorks?” Hailey traced what looked like Central America in dirt on her leg and noticed a burn mark on one of her socks, which was regrettable, but fine. “No. He didn’t try anything,” she said, and wondered for the first time why he didn’t go by his middle name, which was Thomas.

Story: June 2022

June 2022 is a piece of short fiction from Michael Kurt. On a night jog, after finally deciding to forget her past and improve her outlook on life, a woman encounters the very thing that she’s feared most, and the pain is transcendent.

JUNE 2022

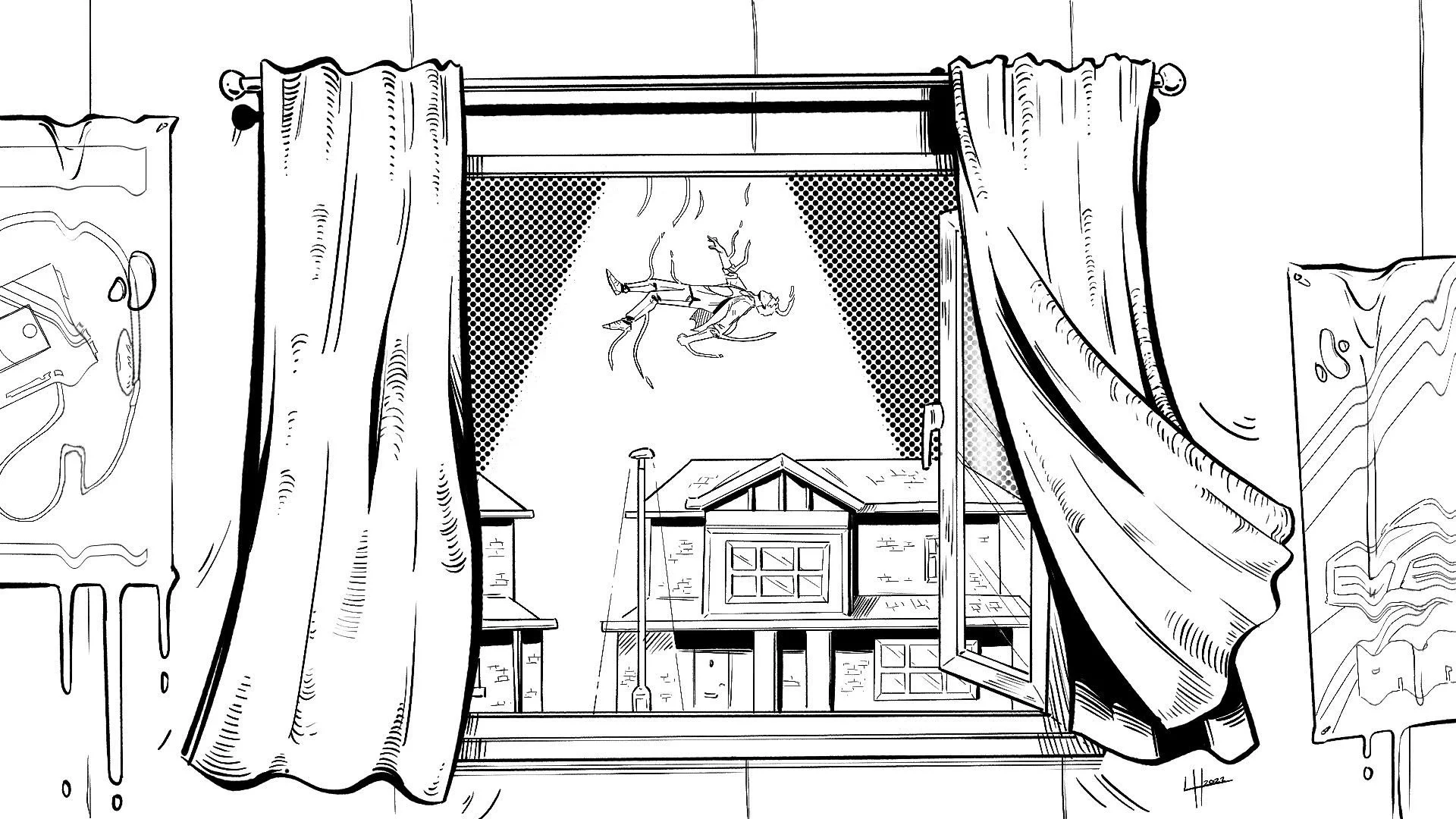

Written by Michael Kurt | Illustration by Laura Helsby

Excerpt:

It was a June night. Almost hot, almost raining, and full of pollen. I thought about turning back for allergy medicine, or a long-sleeved shirt, but knew that if I allowed myself to turn around, I’d allow myself to walk, and then stop, and then go to bed early without stretching or running or manifesting anything. So I plodded along. Doing what I called running. Block to block, I told myself I could make it until the next stop sign without slowing down. There were no cars on our street, or the next street after that. Just even, clean sidewalks. Empty roads.

I could hear myself breathing. It didn’t take long to get winded. After a short stint of confident running, where I felt like things weren’t too bad, I began to feel my true age. Deeply. In my knees and chest. But I tried to keep on anyway, for a few more blocks. Just to the next stop sign.

A cyclist passed opposite me, quickly, barely a blur, and I felt embarrassed to be seen out of breath. It pushed me on, farther, one more block. Then again, another block, for fear of being looked back on from a distance. And it felt good. It felt like progress. Like after however long it had been, I could still make room for health and my own wellbeing; for my aging body and my positive—in the middle of this thought, I was hungry. Not terribly, but suddenly hungry. There wasn’t a breeze, it was calm, and I desperately looked for the cyclist who, just a moment ago, I willed to never be seen by again. Maybe he too was weak and would turn back soon, defeated by the night. The hairs on my neck, then head, then all of my body, rose. I could feel them against my clothes, on end, pushing against the fabric.

I had made it to the stop sign at the end of another block. I tried to read the name of the street, but it melted, green and white, reflective letters, and became unrecognizable streaks on the pavement, pooling, then growing thin, before seeping into the gutter. I grabbed for the pole, but it was below me, and my arms cycled through the empty air before the tree limbs and leaves tore the skin of my hands away. I plowed through the trees wildly; flailing, the hunger growing. Will I be alive?, I thought, passing through bits of trees, after this, crashing along the rooftops and against chimney stacks

June 2022 is a piece of fiction, written by Michael Kurt, whose work includes the short comics Halloween and Sinkhole.

The Illustration for June 2022 was done by Laura Helsby, who is an illustrator and comic book artist from Manchester UK, specializing in black and white inked work. They love anything horror, as well as vintage cassette tapes and vinyl records, especially punk.

"Homebodies" Performance Reading Video

A video performance and reading from the short story “Homebodies.”

Excerpt: "Heaviness Comes With The Night"

An excerpt from the short story “Heaviness Comes With the Night,” which is available now for purchase in the chapbook “Heaviness Leaves The Body.”

1

Casper ducks through the window.

We met in the woods between our houses, late at night. I’m not sure whose idea it was, but we wore an orange bandana around our necks. It was our signal. The path was bare for most of the year, but when the leaves fell you could hide the signal for half a mile if you chose the right place. It started as a game between neighbors.

I’m sick.

“You look terrible,” she says, pushing through the things on my desk, trying not to make noise.

“What are you doing here?” I could be on a different continent, far away; I could leave without a note; I could bury myself deep in the earth, pave it over and build a house and Casper would still find me.

“I brought you supplies, dummy. God knows you don’t have any- thing you need up here in this” – she crouches over a stack of crumpled homework – “hole.”

My room is a sink full of matted hair.

“I’ve managed just fine, thank you,” I say, coughing.

“Right. . .” she says, plowing a collection of used tissues into the trash. “You don’t have to; I can get it tomorrow.”

“What can I say? I like to help,” Casper says. “. . . and right now, you need the most help.”

She looks at the bed but decides to sit at the desk instead. The night air is light in the room, pushing the old sick air out. My head is heavy with fluids and I fall back into the bed. “What we have here is everything you’ll need to recover. This is the good stuff.” She comes from a long line of naturalists. “Ginger, turmeric, black pepper. It burns going down, but it’s worth it.”

“I probably won’t even taste it,” I say, trying to lift my body without coughing.

“Oh, you’ll taste it.” Casper’s always right, which is how we got to where we are now. Distant from each other, existing in silence. I did taste it that night, and for many nights after. Casper laughs; the room brightens. I close my eyes and the fogginess of my entire body lifts. She laughs, I cough, and the world became clear.

2

We’re trespassing in the Harris House Garden, after hours. No one’s watching, so we creep through the front gate; the hinges creak. We laugh in small whispers to each other. We lie in the grass. The chrysanthemums are Casper’s favorite. There are so many of them here.

“Whenever I was sick,” Casper says, cradling the bright flowers, “my grandma used to bring them over in a small jar of water. She said: keep them by your bed and when you start to feel better, burn them in the yard.” She presses the petals into her notebook and writes something I can’t see in a small, tight cursive. “Then the sickness would be gone too.”

Ahead of me, touching the budding ends, soon to bloom, she whispers to herself – or maybe to me, but I can’t hear her. A light comes on in Harris House. People appear at the windows. We didn’t hear them come in (maybe they were always there). Jumping in the hedges, we land clumsily on top of each other, our legs entwine, our arms hold tightly. I can feel the edge of her ribs through her shirt; I try not to touch too much. We lie there for a minute, calming ourselves, trying to breathe softly.

“I think we’re supposed to kiss,” she says, moving slightly so our eyes meet.

I try not to breathe. I try not to move.

“In the movies,” she says, matter-of-factly, “this is where we’d kiss.”

3

“I think this is a mistake,” she says, deep in the forest between our houses. Soon, it will be winter break. Casper was graduating early.

“What do you mean?” I say, almost imperceptibly. “Don’t do this,” she says.

My body feels the end. If I could move, I would take the snow and the rocks and the roots with me. Don’t do this, I tell myself. She moves from one section of the forest to the next, towards her house, away. I try not to follow her. Soon, guests will arrive for a Christmas party I didn’t want to have. Everyone will ask about Casper.

The signal is lost between us. I think this is a mistake, she said, don’t do this. I use the last of my strength to collapse into the house. Later, when guests arrive, I’ll be mistaken for a pile of coats, having never made it past the entryway.

4

There’s a pattern in the cement around the pool. Something that might have been flowers once but wore down into hazy circles. The fence is dark, it blends into the hillside. She’s waiting at the gate. We’ve been fighting for days. About nothing.

Bethany spies on houses in the summer. As the homes empty, and the people escape to the even smaller towns along the coast, she tests the gates and looks through windows. It’s a game I don’t like to play. Or at least, it’s a game I don’t like to play anymore.

“Why don’t you just go out with her again,” she says, tired.

A dark wall of trees surrounds us. For a moment, I consider playing dumb. Who? I’d say. I don’t know what you’re talking about. When Bethany and I met, we talked about Casper leaving (she knows everything), and when we started to date, I felt like I finally had someone I could talk to about all the things I was feeling. For Casper, for love, for loss. At some point I allowed resentment to grow between Bethany and me. It would’ve been easy to avoid, but I didn’t.

I try my best not to sigh and say, “It’s not that easy.”

“Have you tried?”

After Casper left for college, she’d send letters packed with trail maps and brochures from strange museums. She made friends fast and talked about late nights by the campfire over summer break. I put the maps and pictures into a drawer; they became an accordion of colors and time. In my last letter, I remember asking about love and relationships now that she was away from our small town. I tried to make it funny, so it wouldn’t be weird. But it wasn’t that easy.

“I think you’re a good person,” Bethany says, as we turn into her driveway. There are lights on in the house, and windows open, but I know it’s empty.

“We should stop seeing each other,” I say.

“Obviously,” she says, smiling in a sad way I haven’t seen before. “I’m just saying: I think you’re a good person, but you need to figure this Casper thing out. You need to talk to her, or do something, because it’s going to keep getting in the way. Trust me, it’s ruined most of my mom’s relationships. And it’s just...” She ducks to meet my eyes and says, “. . . really painful to watch.”

Bethany pats me on the shoulder and walks to an empty house.

I’m going to tell everyone you’re an asshole, her message says.

I laugh to myself and the forest laughs back. The road is long, and the cars pass in quiet domes of yellow light. I can feel the shirt on the skin of my back, wet and uncomfortable.

5

I wake up alone, in the room where I’ve spent my entire life.

When I was born, my parents bought a small house on a large piece of land by the lake and started building. The original house lives deep in the heart of what stands now. In the living room you can see the boards change color with age.

The lake became our evenings. My father, who worked many jobs, took dinner on the porch, no matter the weather, so he could smoke cigarettes and watch the sun set on the water. In the warmer months we’d join him, if we felt like it. He didn’t mind either way.

When school ended, and Stephen was getting married, my father accepted a job in Albany. At the time, I was looking for a place of my own, so when they offered to leave the house to me, at least for now, I had to say yes. My job at the bookstore wasn’t enough to pay the bills, but they said they’d help. I could get roommates, they said, if I wanted. To not be so alone.

When Casper left, I tried my hand at old cigarettes. Of all the people in town, my father spent the most time on the lake – standing ankle deep looking around, fascinated. In winter, wearing a long coat, he’d return to the warmth of the house, making it smell stale like wet, burning wood. Christmas, for my father, was watching the storms bring the water into the house and batter the windows until it got through, leaking down the sill. And when it would flood, you could hear him laughing from a mile away.

Alone in the house now, loneliness is here with me and the storms. I build a fire and open all the windows just to watch the water pool along the floorboards and seep through, into the space between the house and earth. Wind-torn leaves and the ends of trees come in with the birds to scar the windowsills. When it floods, which is more than before, I comb through the sounds of the night, and the next morning, listening for my father, laughing.

Heaviness Leave The Body Chapbook is available on Gumroad in both physical and digital editions!

Chapbook Digital version is out now!

Heaviness Leaves the Body chapbook is out both in both digital and physical editions.

After messing up the Gumroad page for the digital page, I just decided to release it early!

You can now buy a PDF or ePub version of the full chapbook here:

(if you would like a physical print zine, which are limited to 50 copies, please click here)

My First Chapbook (Print Zine out now!)

In 2019, I decided to collect a few of my favorite short stories into a self-published chapbook zine. The format just felt right. After hemming and hawing for an entire year, the physical editions have arrived and are busy taking up shelf space in my apartment. I decided to self-publish this chapbook of short fiction after many rejection letters from magazines and even more self-doubt. Thanks to the help of my partner and my best friend, it looks great! I could not have designed or presented this book without their help and I am infinitely grateful!

Below is the pre-order information for the physical edition: